BY JEEVIKA WEERAHEWA, DILINI HEMACHANDRA AND DEVESH ROY

The government of Sri Lanka implemented stringent curfew to contain the spread of COVID-19, which disrupted many economic activities. Jeevika Weerahewa, Dilini Hemachandra and Devesh Roy look at the agri-food policy responses including trade regulations, marketing interventions, production and income support programs. They assess how food chains functioned during the lockdown in the island nation of 22 million people-Shahidur Rashid, series co-editor and Director, International Food Policy Research Institute, South Asia.

Colombo and others districts in Sri Lanka remained under curfew as a preventive measure against the spread of the COVID-19: Photo Credit Shutterstock/Ruwan Walpola

After the first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in Sri Lanka on March 11, the government implemented perhaps the most stringent set of control measures. Starting March 20, the country imposed a 24-hour curfew on its 22 million people, relaxed only in low-risk districts twice a week for a few hours. The curfew was partially lifted on April 20, then re-imposed intermittently until May 10. Resumption of civilian life, state and private sector activities is set to begin after that.

This response — which also included closing public schools, ports, and restricting movement across districts — had generally been effective. By May 5, Sri Lanka had 765 confirmed COVID-19 cases and nine deaths, which is much lower per capita as compared to many other countries. However, this stringent disaster management strategy comes with certain costs, leaving a large number of people, particularly in the agriculture and services sectors, without income. In addition, as an island nation with high import dependence, the country is vulnerable to supply chain disruptions.

Overview of Sri Lankan food supply chains

Sri Lanka is self-sufficient in the production of rice, its main staple crop, and mostly self-sufficient in the production of important food items like meat, fish, eggs, vegetables, and fruits. Yet, the country relies on imports for many essential commodities, and with COVID-19 induced disruptions, there may be significant challenges related to these essentials.

The country’s requirements of wheat and red lentils, along with 87% of sugar and 50% of milk and milk products, are met with imports. Chillies, onions, potatoes, and edible oils — all essential ingredients in Sri Lankan cooking — are also largely provided by imports. The country’s key agricultural exports include tea, spices, fresh vegetables, fruits, and fish. Disruptions in export agriculture can have significant effects on incomes and food security (Table 1 and Figure 1 for agricultural trade).

Table 1: Values of Imports, Exports and Trade Balance in 2018, US Dollar Thousand

COVID-19 policy responses

Table 2 presents the timeline of relief measures undertaken in Sri Lanka in response to COVID-19:

The policy responses relating to food supply chains can be summarized in terms of the following five key interventions:

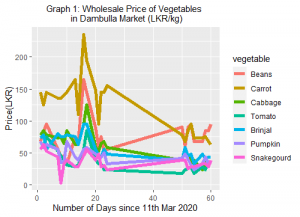

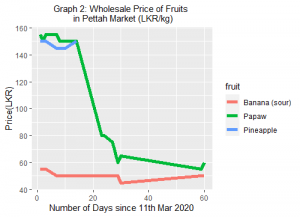

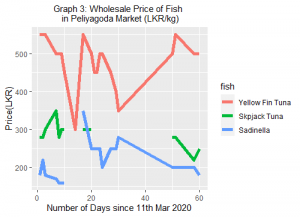

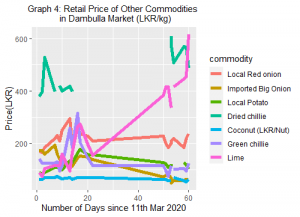

A. Price controls: Unlike its neighbours Bangladesh and India, Sri Lanka does not have a public food distribution system. Thus, managing access to food is through price controls. The government has imposed price regulations on more than 25 items at the wholesale and retail levels. Graphs 1-4 below show the price movement in markets during the COVID-19 pandemic, March 11-April 30. The Consumer Affairs Authority subsequently set the maximum wholesale prices (MWP) for 21 vegetables, sweet potatoes, limes, plantains, and ginger. The maximum markup LKR 40 ($0.21).

With the closure of several public institutions including schools and others, there was a surge in panic buying, particularly in supermarkets. The government introduced a controlled price of LKR 65/kg ($0.34) for red lentils and LKR 100 ($0.52) for a 450g of canned fish for the period March 18-April 30. To offset the effect of price controls, compensation for importers was announced. Maximum Retail Prices (MRP) have been imposed on several varieties of rice, and many retailers were exempted from paying VAT and other taxes. An MRP on Turmeric Powder for LKR 750/kg ($3.90) was also imposed.

B.Provision of essential services, including government procurement of fish, vegetables and fruits: During the nationwide curfew, agriculture was declared as an essential service allowing farmers to engage in production activities. MILCO, the state-owned enterprise responsible for milk collection and processing, also continued its operations during the curfew. Orders for raw milk are collected online and electronic payments are initiated. A guaranteed price for 14 main crops has been imposed along with a government procurement program. On the agricultural input side, agencies are distributing free fertilizers as per pre-existing policy and the cabinet has approved an import of $760 million fertilizers.

A presidential task force comprising administrative department heads at the province and district levels, along with security officials, has been formed to ensure delivery of essential services, including food, with priority to large urban clusters like Colombo, Jaffna and seven others. Like health providers, farmers, food collectors, and distributors have been included in the essential service category. Wet markets and small retailers are important in Sri Lanka’s food distribution while providing an important source of livelihood for the poor. The government-owned Lak-Sathosa stores also engage in food distribution.

The government has introduced several additional exceptions to the curfew, including allowing planting, transportation of planting material, plucking, harvesting, transport for laborers, transport to warehouses, and export activities. Similar measures were introduced for cashews, sugarcane, and export crops like cinnamon, nutmeg, and coffee. Curfew permits were given to distribution agents for food delivery and for transportation and unloading of fish. The state-owned Ceylon Fisheries Corporation has accelerated its fish purchases directly from fishermen and has been allocated $3 million to distribute fresh fish island-wide. Loans up to Rs. 5 million will be provided to farmers at 4 percent interest rate to cultivate 36 varieties of crops including paddy under the New Comprehensive Rural Loan Scheme (NCRCS), the Government announced on April 17, 2020.

C.Home gardening: The government has also encouraged home gardening as part of its COVID-19 response. The Saubhagya (prosperity) home-gardening project initiated at the onset of the crisis, distributed seeds and plants to one million households. A vegetable cultivation drive was also launched to expand production of other vegetables on unused land.

D.Facilitating imports of essential commodities and restrictions on locally grown crops: Given Sri Lanka’s dependence on imports of both agricultural inputs and outputs, the pandemic may pose significant problems for the agri-food system. The government has thus stepped-in to regulate imports of food and agricultural inputs. Per the March 23 directive, Sri Lanka Ports, Customs and other regulatory bodies are instructed to ensure that essential food, fertilizer, pharmaceuticals and fuel reach the relevant supply chain actors. The government-imposed restrictions on importation of locally grown crops to strengthen domestic agriculture.

E.Safety net programs: The government is also working on income support programs, paying $26 (8% of per capita income) to 417,000 senior citizen allowance recipients, to an additional recently-registered 142,000 senior citizens, to kidney patients, and to disabled persons. A monthly payment of $26 is also provided to those who do not have a permanent income. Samurdhi (cash transfer programme for the poor) recipients are given an interest free loan of $52 with a 6-month grace period. Nutritional supplements are delivered directly to expectant mothers and families with malnourished children. Other steps include loan payment deduction, and suspension & relief to private businesses that are unable to pay employees’ wages. Those who do not belong to the above-mentioned categories but who could be at risk are also expected to receive similar relief.

Fallouts due to COVID-19 pandemic

Closure of markets failing to meet hygiene standards: As part of COVID-19 response, Dedicated Economic Centers in Dambulla, Tambuththegama, Nuwaraeliya, Keppetipola, and Embilipitiya were closed due to hygienic reasons. In some areas, farmers were frustrated at having to hold the perishable harvest at home and wait for government procurement.

Disruptions to auction markets in the plantation and export sector: The Colombo Tea Auction, one of the largest and oldest ongoing tea auctions in the world, was suspended for two weeks due to the curfew and e-auctions were established. The first-ever digital sale of Ceylon Tea took place on April 4, and Sri Lanka witnessed its coconut auction via a video conference for the first time. Online coconut auctions —connecting auctioneers, brokers, and suppliers on one platform — have commenced, and similar measures were introduced for rubber, cashew, sugarcane, and other export crops like cinnamon, nutmeg, and coffee.

Disruptions to the food processing industry: Food processing in Sri Lanka is a promising sector with a large share of small- and medium-sized enterprises. It has been disrupted due to falling demand and interruptions in supplies of raw material and labor. In the dairy industry, where most Sri Lankans consume powdered milk, the government has facilitated collection and distribution. Yet, the main constraint for processors remains limited demand for milk-based products like yogurt and the unavailability of raw materials such as starter culture, stabilizers, and packaging material from China. Rice milling was declared an essential service. Food processors were given several concessions in the relief package, including a grace period for tax and lease payments, delayed deductions on loan payments (a debt moratorium of six months), and reduced interest payments on credit cards.

Conclusions

Sri Lanka is often held up as an example among low- and middle-income countries for its effective policy responses to various economic, social and environmental challenges. It is well known for its education and health development policies. On food and agriculture (after initially adopting import substitution like other developing countries), it was the first country in South Asia to rely on open markets involving public and private food sector actors. Having been battered by a long civil war, and enduring the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, the country is probably better prepared to deal with calamities like COVID-19.

The Sri Lankan experience highlights that during a pandemic like COVID-19, keeping the supply chains functioning has been challenging and requires interventions on several fronts. The government has actively applied price policy in the absence of public distribution of food and public procurement. However, the key to food-based programs is to minimize the distortions and employ better targeting.

Jeevika Weerahewa is a Professor and Dilini Hemachandra is a Senior Lecturer at Department of Agricultural Economics and Business Management, Faculty of Agriculture, University of Peradeniya, Sri Lanka. Devesh Roy is a Senior Research Fellow with the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH). The analysis and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors.

This blog has been published as a part of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), South Asia, blog series on analyzing the impacts of the COVID-19’s pandemic on the sub-national, national, and regional food and nutrition security, poverty, and development. To read the complete blog series click here