Poor quality diets are the leading cause of disease worldwide and a primary cause of all forms of malnutrition. Improving diets could save one in five lives annually. However, the extent and nature of the problem varies across contexts and population groups. More than 100 countries use or are developing food-based dietary guidelines as a way to help the public understand how much of which food groups they should be consuming on a daily basis. These guidelines have the aim of promoting healthy eating habits.

Sri Lanka’s food-based dietary guidelines, instituted in 2002 and revised in 2011, use a food pyramid structure with recommended daily servings for each of six food groups. Rice, breads, other cereals, and yams (6-11 servings) are at the base of the pyramid. The second level consists of vegetables (3-5 servings) and fruits (2-3 servings); the third level includes pulses, fish, meat and eggs (3-4 servings); the fourth level contains milk and milk products (1-2 servings); the fifth level is nuts and oil seeds (2-4 servings); and the top of the pyramid is fats and sugars (to be consumed sparingly).

Sri Lankan adult diets are generally marked by high intake of starchy staples—especially rice—and sugary foods, and low intake of fruits, vegetables, and dairy products. In one study, dietary diversity and food variety scores were found to be higher among women as compared to men. However, a recent study found that more than 60% of women in marginalized areas of Sri Lanka did not have minimally diverse diets. In part due to poor quality diets, several forms of malnutrition are prevalent among Sri Lankan adults, including underweight, overweight and obesity, and micronutrient inadequacies. In addition, diet-related non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, are prevalent and are the primary cause of death in Sri Lanka.

To better understand dietary intake patterns among men and women in rural agriculture households, we assessed data from 24-hour multiple pass dietary recalls among adult men and women conducted as part of the baseline of an evaluation of a World Food Programme (WFP) Food Assistance for Assets (FFA) program in Sri Lanka, both with and without an accompanying health promotion process (HPP).

WFP and the Sri Lanka government are implementing the FFA program, which is now in its second phase and called R5N. The program provides cash for labor and physical assets to rehabilitate community water reservoirs used for commercial cultivation, construction of household wells and ponds, and support for livelihood activities such including fish farming and goat rearing. To improve program impact on diet and nutrition outcomes, in some program areas, the Foundation for Health Promotion is implementing the HPP intervention, which focuses on creating conversations around important topics such as dietary practices with the aim of working with people to make small doable changes towards heathier choices.

The baseline data collection for the dietary assessment took place between December 2020 and February 2022. Dietary diversity was scored for each recall following the food group definitions and scoring guidelines recommended by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) for use among women of reproductive age. The ten food groups used in the score are: Grains, white roots and tubers, and plantains; pulses (beans, peas and lentils); nuts and seeds; dairy; meat, poultry and fish; eggs; dark green leafy vegetables; other vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; other vegetables; other fruits. Consumption of oils, snacks, sweets and sugar-sweetened beverages was also assessed, though these categories of foods are not included in the dietary diversity score.

In our study sample, men were more likely than women to have diverse diets in both of the R5N treatment groups (R5N alone and R5N+HPP). However, in the control group, women were more likely to have minimally diverse diets than men (Figure 1). With the exception of women in the control group, at baseline less than 60% of respondents had minimally diverse diets.

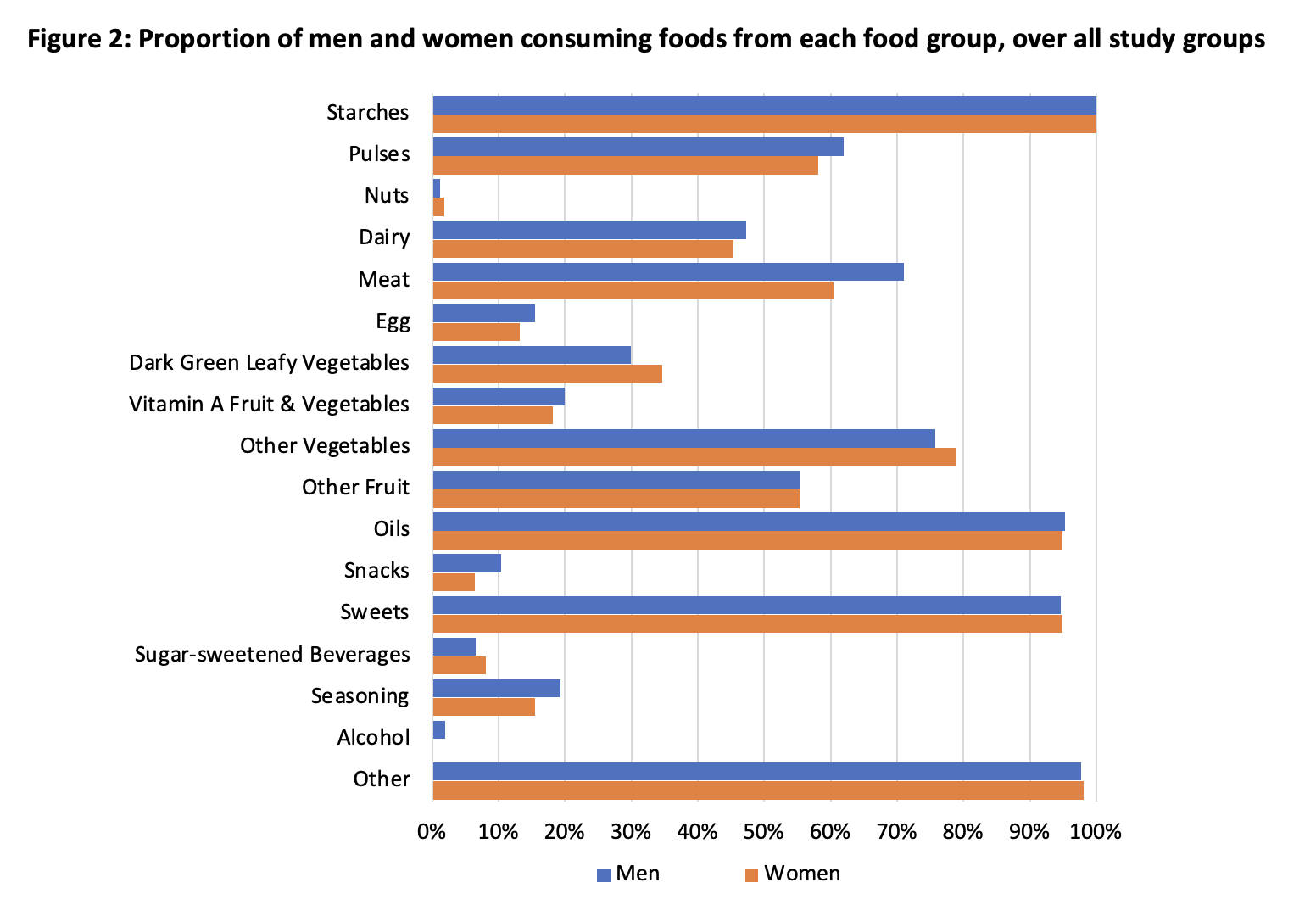

Among the different food groups (Figure 2), the proportion of respondents who had pulses, dairy products, or meat was higher among men than women at baseline, while consumption of dark green leafy vegetables and other vegetables was higher among women than men. Across the sample, all respondents had consumed starchy foods in the previous 24 hours and nearly all had oils and sweets. Intake of vegetables was also commonly reported. More than 70% of both men and women consumed vegetables in the “other” category—such as tomatoes, eggplant or green beans—in the previous 24 hours, about 30% of respondents had dark green leafy vegetables and 20% had vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables such as carrot, pumpkin or mango. More than 50% of respondents reported having had fruits (other than vitamin A-rich fruits) in the previous day. The least commonly reported food groups consumed were eggs and nuts.

The high proportion of respondents consuming starches, vegetables and fruits suggests that the current diet in the study area provides a number of foods from the first two tiers of the Sri Lankan food guide pyramid, while foods from the third, fourth and fifth are less commonly consumed. However, the high proportion of respondents consuming oils (considered fats) and sweets (top tier of the pyramid) suggests that there is a risk of consuming these foods in excess of the food-based recommendations. In future analyses we will assess nutrient intakes of men and women, additional measures of overall dietary quality, and program impact on dietary diversity and nutrient intakes.

Deanna Olney is a Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI's Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division; Bess Caswell is a Research Scientist with the Western Human Nutrition Research Center, Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture; Renuka Silva is a Professor of Nutrition at Wayamba University of Sri Lanka; Malika Fernando is a Nutrition Research Officer with the World Food Programme.

Support for this research was provided by the IFPRI-led CGIAR Research Programs on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH) and Policies, Institutions, and Markets (PIM) and by the World Food Programme (WFP).

This blog was first published here.