On July 15, the Centre issued a notification moving power tillers (PT) and their components from the “free” to “restricted” category indicating a clear intent to provide protection to the domestic industry. Power tillers, also known as two-wheel tractors (2WTs) are tailor-made for the farming landscape in India, dominated by small and marginal farmers. This move is symptomatic of heterodox opening policies, being open on the export side while being closed on the import side. Such policies have long-term unintended consequences. One example is subpar mechanisation and productivity loss in agriculture. It is no coincidence that in South Asia, probably the most mechanised agriculture is in Bangladesh delivering significant productivity gains.

Mechanisation covers the whole spectrum of activities from land preparation, threshing, harvesting storage and even transport. India’s mechanisation coverage is around 40-45 per cent, compared to 90 per cent in developed countries. If productivity in agriculture and incomes of farmers were to go up significantly, Indian agriculture must hit the mechanisation frontier.

Some of the need for mechanisation follows the natural course of rising rural-urban migration. The impacts of mechanisation are however more far-reaching. New trade economics teaches us that farmers would be successful in trading or accessing markets only when highly productive, which beckons large scale and intensive mechanisation. History has given ample proofs on the power of farm mechanisation. As an example, why did villages grow into cities in West Africa? It happened when food sufficiency happened due to the growth of ironworking. Noks living in present-day Nigeria made iron tools learning from traders who crossed Sahara coming from Europe. With iron tools, farmers could clear land and cultivate crops more efficiently than with stone tools. The Hittites of present-day Turkey were the first to master ironworking long ago.

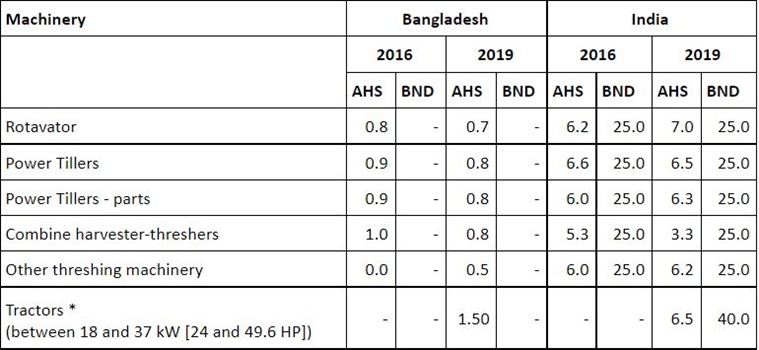

Come 2021, the role of trade in the mechanisation of agriculture remains as potent. Comparatively high tariffs on agricultural machinery, placement under restricted trade hits the cog in the wheel of mechanisation. Table 1 shows that (applied and bound) tariffs on agricultural machinery are 8-10 times higher in India. High bound tariffs discourage trade in a dynamic sense.

Table 1. Average tariffs (percentage) on four main agricultural machinery  Note: Tariffs for tractor with 30-50 HP, the dominant type in India are shown. [Source: World Integrated Trade Solutions (TRAINS)]

Note: Tariffs for tractor with 30-50 HP, the dominant type in India are shown. [Source: World Integrated Trade Solutions (TRAINS)]

The average cost of imported PT in India is between Rs 70,000 and 80,000, and tariffs, increases it up to Rs 85,200. With handling charges, social welfare surcharge and other duties, the import parity price is near equal to the average cost of locally manufactured PT, that is, Rs 92,000.

Secondly, a shift to restricted category and frequently changing tariffs engenders uncertainty and lowers trade. It also disincentivises domestic machine manufacturers to invest and innovate — the perils of protection.

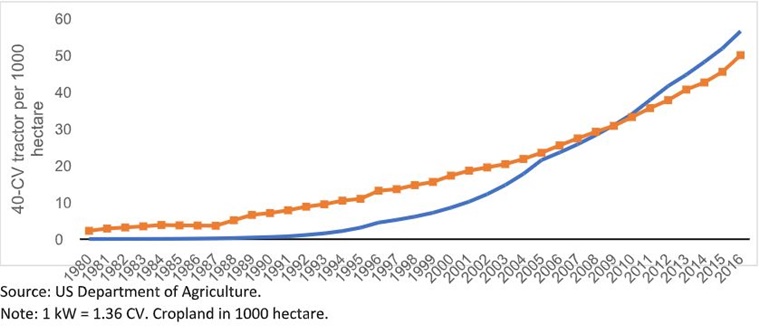

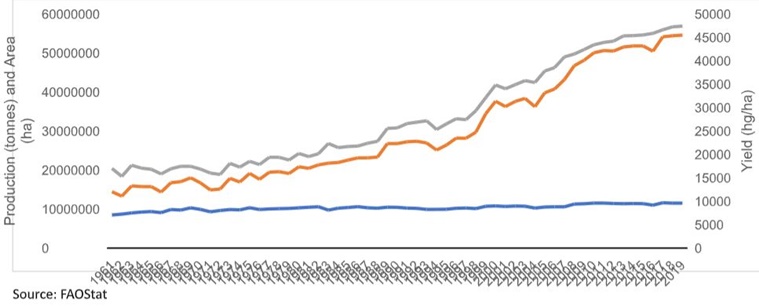

Among different lessons that Bangladesh offers in industrialisation and commerce, farm mechanisation is likely the untold story. A perfect example of orthodox opening in the late 1980s, Bangladesh removed import bans on PT and other machinery like diesel engines. By 1995, PT were made duty free and credit support was provided for purchases. Figures 1 (power use in harmonised units across machinery) and 2 (productivity patterns in rice) capture the effects of such openness. Starting lower, Bangladesh overtook India in mechanisation by 2006. From the late 1980s, increases in utilisation of power occurred in both countries, from 1990, at 16 per cent in Bangladesh and 7 per cent in India. Studies have credited PT in increasing the rice yield, which grew 2.1 per cent annually from 1990, compared to 1.6 per cent between 1960 and 1989.

Figure 1. Trend of mechanical power in agriculture

Figure 2. Rice area, production, and yield in Bangladesh

Note: hg = hectogram and ha = hectares.

At present, only Punjab, Haryana and western UP have mechanisation rates between 70 and 80 per cent whereas in eastern and southern states it is between 35 and 45 per cent, with even smaller coverage in North-Eastern states. Liberal and stable trade policies will increase access, competition will expand varieties and bring down the prices. Bangladesh also shows the role of complementary policies such as credit support. Once the farmers achieve sufficiently high productivity, they can access markets and even integrate with GVC if allowed by policy as intended in the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Act, 2020. Liberal trade in machinery presents an opportunity to access distant and international markets. The key is to be both ways open.

Manmeet Ajmani is a Research Analyst and Devesh Roy and Hiroyuki Takeshima are both Senior Research Fellows, at IFPRI. This op-ed was originally published in The Indian Express.

The views expressed in this article are solely of the authors.