Being social is important for women’s mental health: Insights from a pre-pandemic survey in rural India

Women in rural India have always experienced a high and growing incidence of common mental disorders, and often have no or little recourse to treatment or support. The additional stressors that COVID-19 has introduced, such as constant worry of infection and loss of income and livelihoods, among others, are likely to further exacerbate this situation. By using cross-sectional data from a pre-pandemic survey of rural women across five states, the authors provide evidence of factors associated with mental health that include shocks to non-farm livelihoods, women’s access to the support of self-help groups, and household food insecurity. Measures to change these levers could help reduce the weight of mental burdens that women currently bear — Kalyani Raghunathan, series co-editor and Research Fellow at IFPRI

Shutterstock/Sk Hasan Ali

The pandemic has likely deepened mental health issues in India

Imagine being a 26-year-old mother and working as a farmer in rural India. Besides your usual concern about earning enough income to feed your children, you also have to worry about repercussions of COVID-19 on your health and livelihood, and take appropriate preventive measures. Would this increase your anxiety levels?

While we don’t yet know the complete extent to which the pandemic has affected the mental health of Indians, the 2003 Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome epidemic is reported to have led to a series of mental ailments, ranging from anxiety to depression to suicidal behavior. In India, an April 2020 phone survey of 413 low-income households in Delhi found that 65% of female respondents reported feeling depressed and 75% felt anxious or nervous about their situation. This is especially worrisome given that even in the absence of a pandemic, an estimated 1 of 7 Indians suffer from mental disorders of varying severity and mental disorders have been increasing at an alarming rate in the last three decades in the country.

The question that arises now is what can be done to respond to India’s burgeoning mental health crisis, particularly in the hard-to-reach rural population that already suffers from a huge and unmet gap in mental health services.

Our survey in rural India on predictors of mental health

Our recently published paper on predictors of common mental disorders (CMD), from a sample of 1644 mothers living in rural India, can provide some initial insights into potential policy levers. In 2017, we conducted a cross-sectional survey in 158 villages in eight districts across five Indian states (Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Odisha, West Bengal, and Chhattisgarh). We used a validated non-diagnostic tool, the 20-item Self-Reporting questionnaire, to screen for CMDs. We examined factors associated with CMDs across six dimensions: women’s work, women’s agency, women’s health and nutrition, child health, household social status, and experience of shocks.

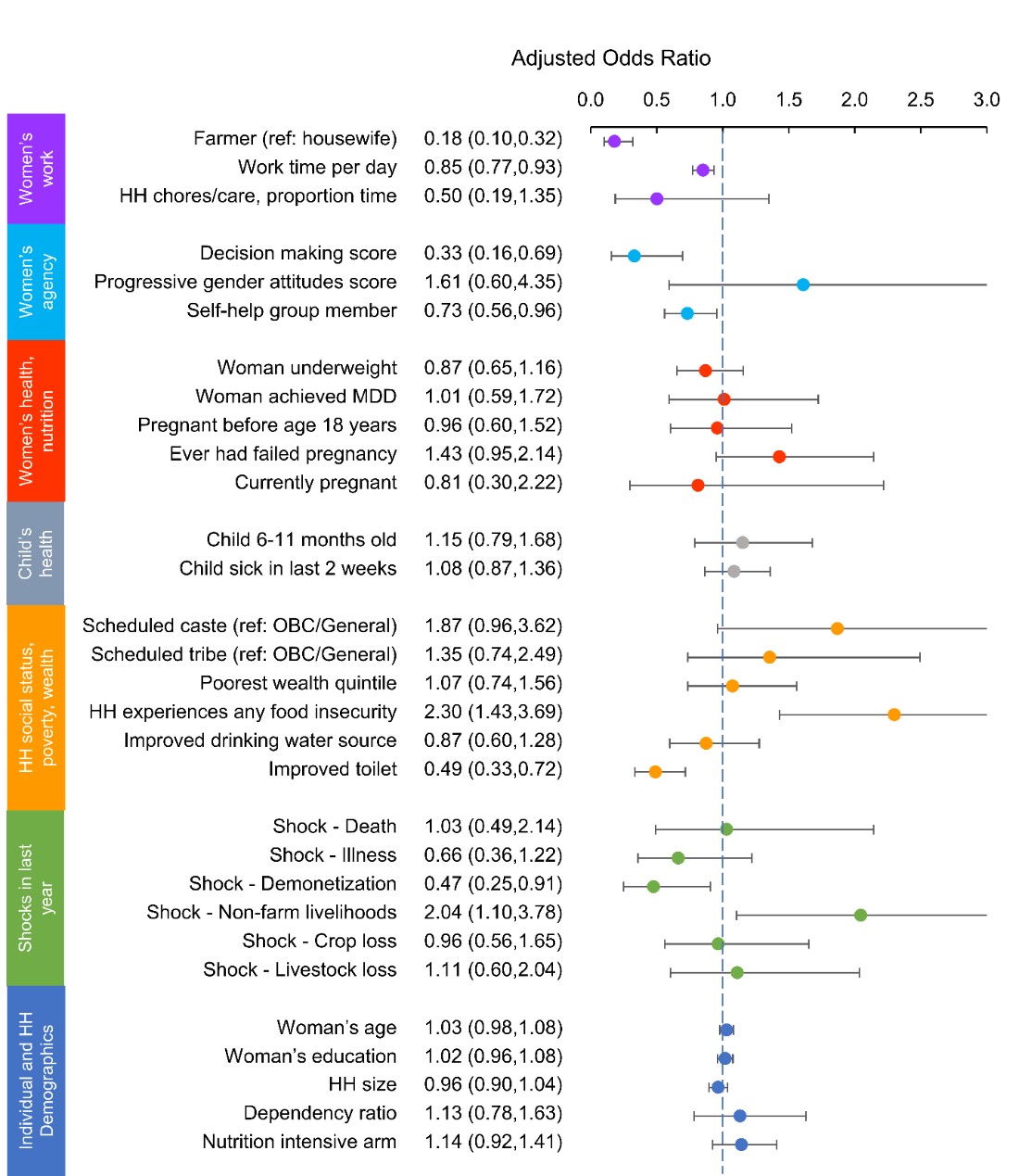

Our findings highlight that mental health among mothers of young children in rural India is associated with multiple factors (Figure 1), underscoring the complexity of addressing CMDs in this setting. Here, we highlight three key findings that have implications for the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1: Factors associated with symptoms of CMDs in Indian women with children aged 6-24 months. This figure is from the authors’ paper published in PLOS ONE. The outcome is a dummy indicator for CMDs. Dots represent odds ratios adjusted for all other factors shown. 95% confidence intervals are represented by horizontal lines. A factor is statistically significant if the confidence interval does not cross the dashed vertical reference line at 1.0. If the odds ratio is less than 1.0 (e.g. self-help group member), the factor is a protective factor, e.g. women who are self-help group members had lower odds of reporting CMDs than women who are not self-help group members. If the odds ratio is greater than 1.0 (e.g. shock to non-farm livelihoods), then the factor is a risk factor, e.g. women from households that experienced shocks to non-farm livelihoods were more likely to report CMDs than women from households that did not experience these shocks.

Key finding 1: Shocks to non-farm livelihoods are associated with poorer mental health

One finding that stood out was that women from households that had experienced shocks to non-farm livelihoods (i.e. loss of employment or business failure) in the past year were twice as likely to report CMDs than women from households that did not experience this type of shock in the past year. The long-term impacts of COVID-19 on livelihoods are yet to be realized, but economists have predicted that around 40 million Indians have lost their jobs following the national lockdown. It is not surprising that a shock of this nature would be associated with poor mental health.

Key finding 2: Self-help group membership is associated with better mental health

A second noteworthy finding was that women who were self-help group (SHG) members were 27% less likely to report mental health problems than women who were not SHG members. While SHG meetings are currently suspended to comply with physical distancing requirements, this finding suggests that India’s widespread SHG movement could play an important role in supporting women’s mental health. SHGs may act as mental health havens where women can discuss their problems and get connected to resources to support their overall wellbeing. It is imperative that we find ways for SHGs in rural areas to adapt to the new normal. Now more than ever, women need to find a way to continue supporting each other.

Key finding 3: Living in a food insecure household is associated with worse mental health

The way forward: Address the underlying determinants of well-being

During normal times, many women in rural India rely on the support of self-help groups for accessing credit, increasing their political participation and increasing their sense of empowerment. Reassuringly, non-governmental organizations involved in promoting women’s groups are already adapting to the new challenges posed by the pandemic. Evidence on how the virus is transmitted suggests that local organizers can continue SHG meetings if they reduce the size of their groups, follow physical distancing rules, use masks, and meet in outdoor spaces.

Life is not expected to return to normal in the foreseeable future and recovery from the massive shock to livelihoods is likely to be a long road ahead. In addition to the emergency response necessary to boost mental health resources in rural India, the research community must better understand how mental health problems can be prevented in the first place. Ensuring that social safety nets reach the resource-poor and food insecure households may play a key role in mitigating a post-pandemic mental health crisis in India.

Alejandra Arrieta is a PhD candidate at the University of Washington. Samuel Scott is a Research Fellow, Neha Kumar , Purnima Menon and Agnes Quisumbing are Senior Research Fellows at IFPRI’s Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division (PHND) . The views and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors.

This blog has been published as a part of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), South Asia, blog series on analyzing the impacts of the COVID-19’s pandemic on the sub-national, national, and regional food and nutrition security, poverty, and development. To read the complete blog series click here

New research from a Special Issue of Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy

The pandemic caused disruptions to both the supply of and demand for health services that persisted past the lifting of lockdown measures.

Public food transfer programs have traditionally been the most common social protection programs in Bangladesh