Indian diets fall short of EAT-Lancet reference recommendations for human and planetary health

Girls visit a snack vendor in Mumbai. The ubiquity of snack foods in India is contributing to a rise in overnutrition. PC: Adam Cohn/ Flickr

Many developing countries face a double burden of malnutrition, where the prevalence of obesity and noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) linked to overnutrition are rising while undernutrition persists. In India, this phenomenon is a serious threat to public health: Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death while dietary iron deficiency is the biggest contributor to disability.

In 2019, the EAT-Lancet Commission on Food, Planet, and Health proposed a global reference diet aimed at providing adequate nutrition for 10 billion people in 2050 within environmental limits. Though the recommended diet is not always optimal for the context of developing countries, it can help to show where Indian diets fall short in terms of nutrition and suggest areas of improvement. These recommendations can help policymakers navigate the complex food system as it faces new challenges such as changing diets and climate change.

In a research paper published in BMC Public Health, we compare the EAT-Lancet diet’s recommendations with Indian diets across Indian states and income levels using data collected by the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) in 2011-12. (This is the latest data available; the 2018-19 survey was scrapped because of data quality issues.) The findings show that compared to the reference diet, the average Indian diet is considered unhealthy, with excessive consumption of cereals, processed foods, and snacks, but not enough protein, fruits, and vegetables. In fact, diets in all Indian regions, income groups, and urban and rural sectors generally exhibit these alarming trends.

Affordability plays a large role in shaping Indian diets. India’s current food policies and budget allocations are focused primarily on keeping staple products such as rice, wheat, and sugarcane affordable through high subsidies and trade regulations. Thus, these crops—easy to grow, yet unhealthy if consumed to excess and often environmentally detrimental—dominate the market and make up a large portion of the average Indian diet. For example, though the EAT-Lancet report recommends that only a third of total calorie intake come from whole grains, they represent up to 70% of some households’ diets.

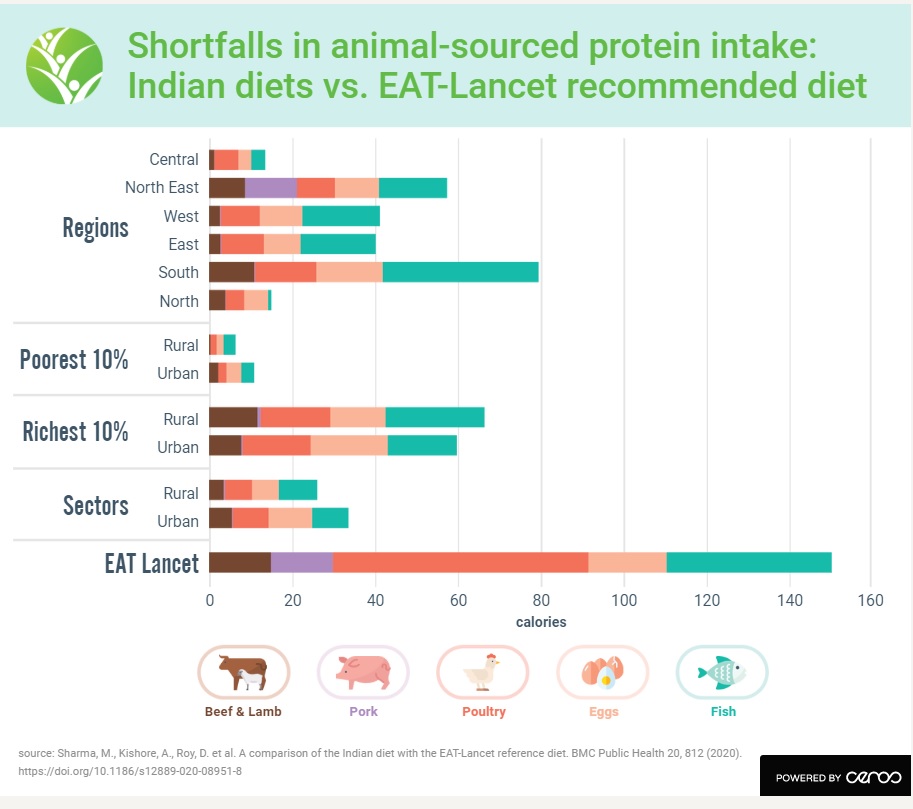

The costliness of high quality, nutritious foods relative to staple grains also places a burden on many consumers. As a result, there is a serious calorie intake deficit of vegetables, fruits, legumes, and animal sourced proteins in the Indian diet compared to the reference diet. For instance, the poorest Indians get fewer than 130 calories from protein sources (both plant- and animal-based) per day, less than 20% of the recommendation.

But even the richest in India consume only half the amount of protein that the EAT-Lancet diet recommends, indicating that costs are only part of the cause of nutrient-deficient diets. Some possible explanations include a lack of availability, accessibility, awareness, and acceptability.

Dietary preferences can offer some insights. The EAT-Lancet report recommends consuming only very small amounts of processed foods, including snack foods; in fact, the reference diet does not even categorize these as a separate food group. These types of foods, typically high in sugar, salt, saturated fats, and processed flour, are considered unhealthy and linked to many diet-related NCDs.

Yet processed foods account for almost 30% of the richest urban households’ daily calorie intake and 10% of the average household’s (see graphic). The high consumption of processed foods can stem from cultural preferences (e.g. savory snack foods, known as namkeens, and semolina, or suji, used in a variety of processed foods including desserts) and Western influence (e.g. chips, jelly, ice cream).

High consumption of processed foods offers a partial explanation of India’s rising prevalence of obesity —despite a low total calorie intake compared to the reference diet. Our results show the Indian total calorie intake is approximately 2,200 calories per day, 12% lower than the EAT-Lancet reference diet’s recommendation of 2,500 calories. We also believe that insufficient levels of physical activity contribute to the phenomenon, as the EAT-Lancet diet is developed for individuals with moderate-to-high levels of activity, and more than half of all Indians are physically inactive. Thus, lifestyle and diet choices are a critical factor that policy makers must address to better the nation’s public health.

The Indian food system requires a major transformation to promote diets that are healthy for both the planet and people. Even if Indian diets are not composed exactly as the EAT-Lancet commission recommends, the comparison makes it clear that change is needed. On the supply side, existing food policies should be readjusted to provide more incentives for farmers to produce fruits, vegetables, and animal products, making more healthy options available at affordable prices. On the consumption side, raising awareness about the need for more diverse diets, subsidizing healthy products, implementing cash transfers to address affordability issues, and organizing communication campaigns can encourage households to shift their eating habits towards more nutritious options. A comprehensive policy approach that considers affordability, availability, accessibility, awareness, and acceptability can close the nutrition gap and prompt Indians to eat diets that are healthy and sustainable for all.

Manika Sharma is a Program Manager with the IFPRI-led CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH) based in New Delhi; Avinash Kishore is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s South Asia Region (SAR) office in New Delhi; Devesh Roy is an A4NH Senior Research Fellow based in New Delhi; Kuhu Joshi is an IFPRI SAR Research Analyst;Khiem Nguyen is an IFPRI Communications Intern.

This blog was originally published in ifpri.org here