As the health and economic impacts of COVID-19 continue to evolve, researchers have been using new and creative methods of data collection. Widespread use of approaches such as computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) has generated enthusiasm for phone surveys to eventually replace face-to-face fieldwork in the long run as a cheaper and faster alternative. But how well do phone surveys perform in terms of response rates, response bias, and data quality—particularly for women respondents?

As the health and economic impacts of COVID-19 continue to evolve, researchers have been using new and creative methods of data collection. Widespread use of approaches such as computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) has generated enthusiasm for phone surveys to eventually replace face-to-face fieldwork in the long run as a cheaper and faster alternative. But how well do phone surveys perform in terms of response rates, response bias, and data quality—particularly for women respondents?

Early results from our phone surveys in India suggest that CATI poses several challenges to obtaining reliable and quality information, especially when collecting sensitive data from women and potentially other vulnerable groups. Moreover, the inability to ensure privacy of the respondents, which is heightened during COVID-19, might expose them to risks.

In partnership with Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), we conducted phone surveys in 9 districts of Gujarat, India with over 600 SEWA members to assess the impact of COVID-19 on incomes and livelihoods, household care duties, food and water security, intra-household decision making of women, and household conflict. The study covered SEWA members engaged in a variety of livelihood activities in rural and urban areas. The surveys were conducted during the lockdown in Gujarat from late May to mid-June, with significant restrictions on movement of individuals, goods, and services. This was the first in a series of 5 surveys intended to track short to medium term impacts of the pandemic and to trace the evolution of household resilience strategies. The aim is to conduct the remaining 4 surveys as the state starts unlocking and relaxes restrictions on movement and key activities.

We selected respondents from among SEWA membership lists, and SEWA staff contacted them in advance, telling them to expect our call. To ensure that respondents felt comfortable answering questions over the phone, the survey team was made up almost entirely of female enumerators, many previously affiliated with SEWA. Having enumerators familiar with the workings of the organization helped build rapport with the respondents. As enumerators were familiar with SEWA livelihoods and local procedures, they were also able to provide valuable insights that improved the articulation of survey questions. Despite this seemingly ideal set up, several challenges were encountered during implementation.

Reaching women by phone

It was apparent from the outset that good quality cellphone devices and reliable internet connections (for uploading data) at the enumerators’ end were critical. On the respondent end, cellphone network challenges affected our ability to reach several rural women. The larger challenge, however, was reaching women who either did not have their own cellphones, or whose phones became inactive between the time they were recruited and when the survey was conducted. The digital gender divide in access to cellphones and internet is widely documented and is highest in the South Asia region.

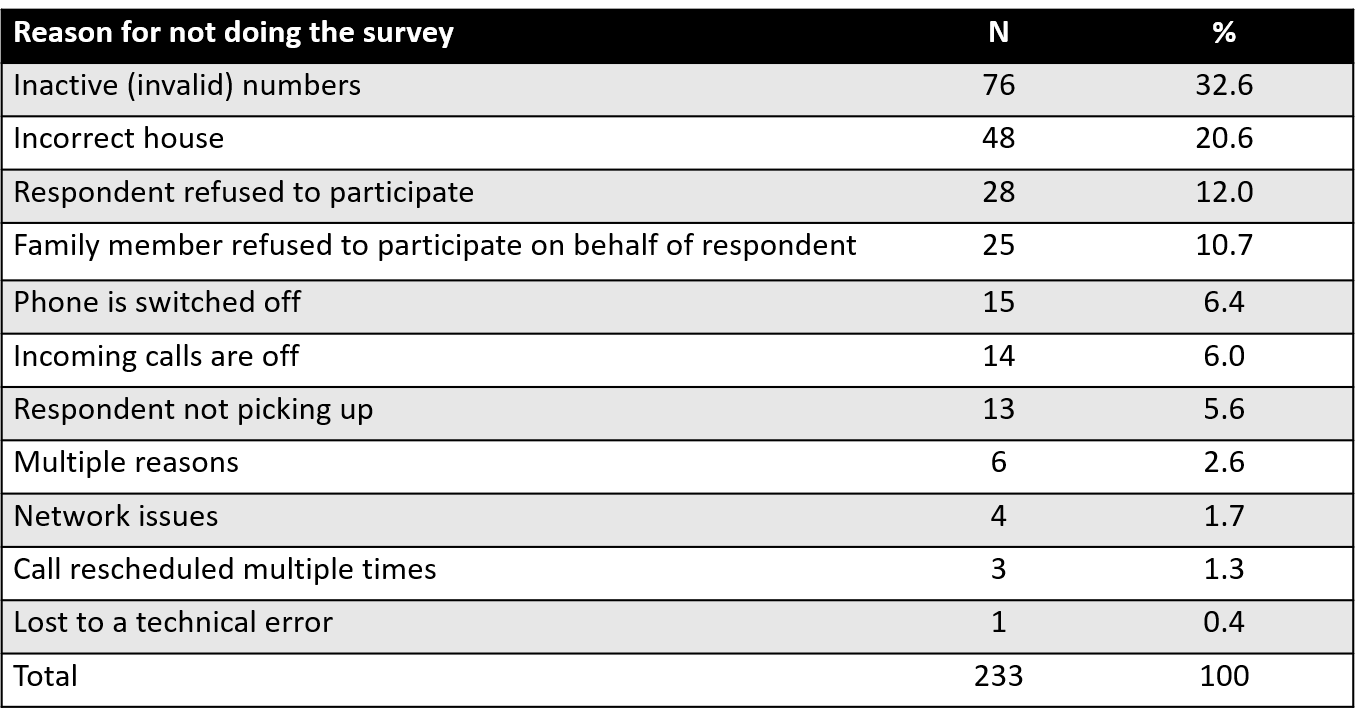

In addition to gendered ownership, we also found that women’s phones were less likely than men to have airtime during COVID-19, affecting response rates. We found that, as households faced income losses, women’s cellphones were one of the first expenses to be cut from the household budget. Of 930 respondents, 25% could not be reached (Table 1); half of the women who could not be reached had phone numbers that had been deactivated or wrongly recorded. Finally, even though all SEWA members who were contacted had earlier agreed to participate in the survey, during implementation, nearly 23% of respondents or members of their family declined to participate.

Table 1: Reasons why a respondent could not be contacted

Ensuring safety and confidentiality during the conversation

Ensuring that responses remain private and confidential and cause no direct or indirect harm to respondents is critical for any survey, but especially challenging in phone surveys. We had been forewarned by SEWA that in recruiting respondents for the survey, they noticed that several women were answering the phone while on speaker, sometimes on their own volition, but often as a result of a request by spouses or in-laws. This was important information to have beforehand, not only to factor in response bias and interpretation of findings, but also to ensure that sensitive questions on intra-household conflict were not asked. In our sample, 65% of the respondents had their phones on speaker for at least some portion of the survey.

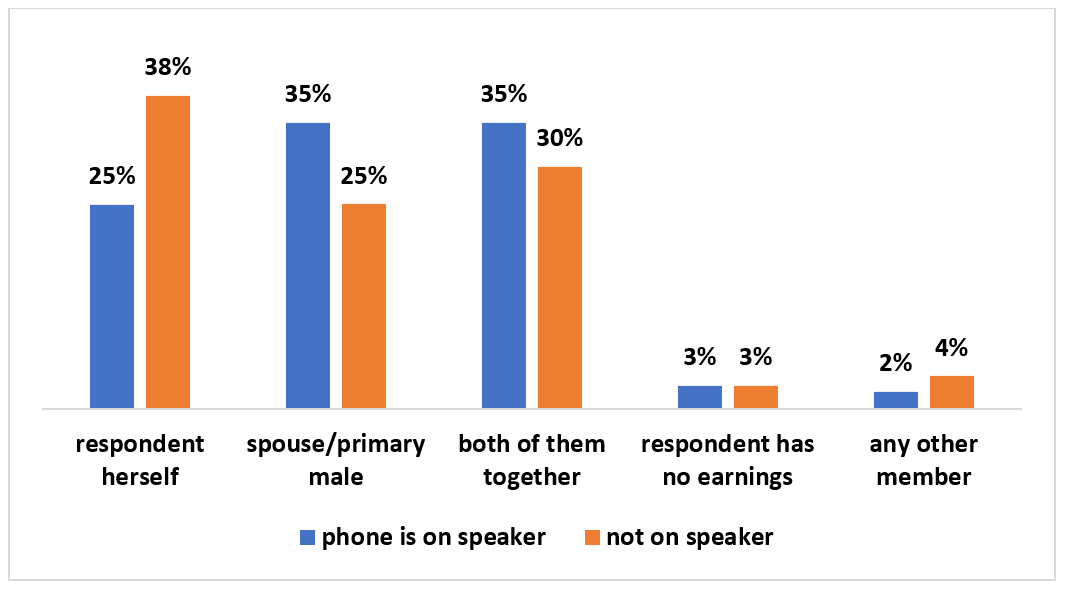

Collecting data on sensitive questions such as intra-household conflict might expose women to risks if someone is listening in. Respondent privacy was therefore critical for both respondents’ safety and data reliability. In our first survey round, we asked the conflict module to only 220 out of the 620 respondents, who were in a private space and did not have their phone on speaker. This meant not only that the data on conflict were non-representative, but also that the large sample with phones on speaker might have provided biased responses to modules on intra-household decision making, care duties, and control over income and assets. For example, we found that when the phone was on speaker, women were more likely to report their husbands as the primary decision-maker on earnings (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Who decides how to spend respondent’s earnings

Note: Sample size is 627. All respondents were asked this question irrespective of whether they were employed or not, in order to account for other sources of personal income or earnings.

Making the conversation count

A further challenge of CATI surveys is non-response. Face to face (FTF) interviews are more amenable to collecting data by allowing enumerators to build rapport, respond to visual, verbal, and facial cues, and make changes on the spot.

Poor cell phone connection is a further impediment in some areas and poorer, more vulnerable women are less likely to have access to a phone or to be in a private space. Finally, random sampling remains a challenge when the final sample is driven by differential access to a phone.

To call or not to call?

While FTF interviews remain a challenge till the time social distancing norms continue to be enforced, telephonic interviews can be a viable, albeit imperfect, alternative. Phone surveys can yield quick snapshots of the experiences that women and men face as a result of a shock, such as COVID-19, and can help inform programming that targets key vulnerability experiences linked to the specific shock.

However, when reporting results from telephone interviews, it is important to describe the sampling strategy as well as the challenges encountered in terms of women and men being able to freely respond. This will help better understand how respondents and their responses might have been affected by their gender, age, minority status, income level, and the survey mode itself.

Authors

Muzna Alvi is Associate Research Fellow and Shweta Gupta is a Research Analyst at IFPRI’s Environment, Production and Technology Division (EPTD), based in New Delhi, India. Ruth Meinzen-Dick is Senior Research Fellow with IFPRI’s EPTD and Claudia Ringler is EPTD Deputy Director. The analysis and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors. We thank the enumerators at AIDMI and all the SEWA members for providing their time for these phone surveys. This study was funded by the Federal Government of Germany (BMZ) with support from the CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions and Markets (PIM) led by IFPRI.

This blog was originally published on the website of CGIAR Research Program on Policies, Institutions and Markets (PIM)

This story is part of the EnGendering Data blog which serves as a forum for researchers, policymakers, and development practitioners to pose questions, engage in discussions, and share resources about promising practices in collecting and analyzing sex-disaggregated data on agriculture and food security.

If you are interested in writing for EnGendering Data, please contact the blog editor, Dr. Katrina Kosec.

Photo: © Simone D. McCourtie / World Bank

New research from a Special Issue of Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy

The pandemic caused disruptions to both the supply of and demand for health services that persisted past the lifting of lockdown measures.

Public food transfer programs have traditionally been the most common social protection programs in Bangladesh