Lockdown and Rural Distress: Highlights from phone surveys of 5,000 households in 12 Indian states

Designing relief measures is dependent on the availability of primary data on how households are coping with the economic uncertainties brought about by COVID-19, and the subsequent economic lockdown. Using survey data collected from 5,000 households across 12 states, the authors show that households with returned migrants are worse off than others, and have had to resort to strategies related to adjusting their food habits, borrowing to finance expenditures, and selling productive assets, all of which have medium- to long-term consequences. In addition, women seem to be bearing the brunt of this distress, with significant increases in their workload. Special attention needs to be paid to these two groups if relief is to be targeted effectively. – Kalyani Raghunathan, series co-editor and Research Fellow at IFPRI

Mumbai: migrant worker stand in queue to collect registration form, to travel back to their homes during nationwide lock down PC : Shutterstock/Manoej Paateel

Economic activity in India came to a grinding halt as the nation-wide lockdown came into effect on March 25, 2020. The immediate consequences of this measure were felt by the urban poor. So, while rural India was in the beginning relatively unaffected by the virus, life and livelihoods in rural areas have not been immune to the lockdown. To broadly understand the effects of COVID-19 on rural households, especially those with returned migrants, a rapid survey was undertaken in the last week of April 2020.

In this blog, we focus on two aspects of our survey of rural Indian households – coping strategies and the effects of the lockdown on women in the household. Given the restrictions on mobility and the need to maintain distancing, the survey was conducted through rapid phone interviews. The survey, implemented by a group of civil society organizations, covered 5,162 rural households in 48 districts in 12 states: Assam, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Bihar, Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Rajasthan. The sampling strategy was purposive, and 2 blocks were chosen in each district, with 5 villages per block, and 10 households per village.

Coping with shocks: Households with ‘returned migrants’ are worse-off

With the onset of lockdown, somewhere between 5 and 30 million migrants decided to return to their rural homes. Our survey was conducted just after the first wave of reverse migration. Hence, we compared the coping mechanisms of households with and without returned migrants.

The literature on coping – largely emerging from the famine – shows that in times of stress, households tend to have a repertoire of actions in which they try to preserve assets most important to their livelihood. Usually coping strategies start with changes in food habits and a reduction in discretionary expenses. If the stress continues or intensifies, there is an increased reliance on borrowing, followed by sale of productive assets such as land and livestock (Jodha 1972, Corbett 1988, Davies 1996).

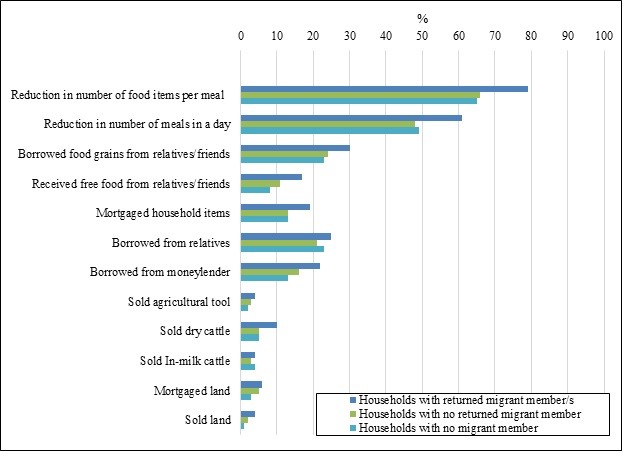

We compared responses for three groups of surveyed households: households with a returned migrant member (n=734, 14%), households with a migrant member who had not returned (n=3516, 68%), and households with no migrant member (n=921, 18%). We found that households were already engaging in several coping mechanisms (Figure 1). Many households were reducing the number of food items in a meal and the number of meals in a day. Further, households were borrowing food grains and food from relatives or friends, underscoring the importance of strong social networks in rural society. Our findings are in line with ground reports that rural India was already eating less food and inferior food.

Figure 1. Coping mechanisms of rural Indian households to the COVID-19 shock by migrant status

Source: Phone survey of 5162 households across 12 states conducted in the last week of April 2020

Some households also had to mortgage household items or borrow money from relatives or moneylenders. Since the lockdown was still in its first month at the time of the survey, we did not expect to find households that had already started disposing off their productive assets. However, this was seen among few households, suggesting that their experience of the shock was intense.

Households with returned migrant members reported higher rates of distress than households with migrants yet to return or no migrant members (Figure 1). This was true in terms of adjusting food habits, borrowing, and sale of productive assets. These findings are unsurprising. As per the 2007-2008 migration survey by National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO), remittances from migrant members accounted for 40-50% of the annual expenditure of rural households. It is likely that migrants who returned from cities in March and April came back empty-handed, thus reducing the purchasing power of the rural household.

Impacts on livelihoods were also felt in dairy and poultry sectors. Nearly half the households working in the dairy sector reported a fall in the sale of milk, and 42% households in the poultry business reported a fall in the sale of poultry birds. Given this widespread distress, it was heartening to find that the Public Distribution System (PDS) has emerged as an important source of food grains during the crisis period. More than 80% surveyed households reported their dependence on PDS for their food grains. However, 79% surveyed households, who reported using PDS, also depend on village markets for food requirements, which is unsurprising, given the limited types of food provided by the PDS.

Women shoulder the increased burden of rural distress

Return migration and the consequent increase in the number of household members could have multiple implications on women’s workload and their quality of life. To assess the effect on workload, we looked at access to water and access to wood for fuel, the burden of which is primarily borne by women in most households in rural India.

Among households that need to collect water from outside the home, 47% reported that female members were spending more time fetching water. Similarly, among households using wood for fuel, 50% reported that the female members were spending more time collecting firewood at the time of survey, as compared to earlier in the year. Part of the increase in time to collect water and fuel may be seasonal as April is one of the hottest months of the year in India. Households with returned migrant members were more likely to report a higher workload for women, with as many as 40% households reporting an increase, as compared to only 24% in households with no returned migrant member, and 19% in households with no migrant member.

Conclusion

Our survey provides an incomplete but telling snapshot of the situation among rural households, one month into India’s lockdown. Though COVID-19 was not yet widespread in rural areas in late April, livelihoods were already facing stresses resulting from the lockdown-induced economic slowdown. Our two key findings are that households with returned migrants were doing worse than households with unreturned migrants and no migrant members, and that women were facing the brunt of the increased workload. These are ominous signs. Since the time of the survey, many more thousands urban migrants have returned to their villages. As policymakers attempt to enhance the resilience of rural communities by rebuilding lives and livelihoods, special attention must also be paid to households with returned migrants and the extra burden borne by women.

We acknowledge the help of all the villagers we approached for the study, who gave their valuable time and input in these extraordinary times. We acknowledge the help of BAIF, PRADAN, AKRSPI, ASA, Grameen Sahara, SATHIUP and TRI in partnering with us on survey implementation. We are indebted to Sridhar A. for managing the logistical arrangements of the survey.

Kiran Limaye is a Researcher at VikasAnvesh Foundation, Pune. Dharmendra Chandurkar is a Co-founder of Sambodhi Research and Communications. Nirmalya Choudhury is a Senior Researcher at VikasAnvesh Foundation. The analysis and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors.

This blog has been published as a part of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), South Asia, blog series on analyzing the impacts of the COVID-19’s pandemic on the sub-national, national, and regional food and nutrition security, poverty, and development. To read the complete blog series click here

New research from a Special Issue of Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy

The pandemic caused disruptions to both the supply of and demand for health services that persisted past the lifting of lockdown measures.

Public food transfer programs have traditionally been the most common social protection programs in Bangladesh