Reduced food and diet quality, and need for nutrition services during COVID-19: Findings from surveys in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh

Do poor households in the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh have enough food during the lockdown? Have they changed the types of foods they eat? Have consumption patterns changed differently for men and women? Are nutrition services reaching households? Rajib Acharya sheds light on these questions using data from surveys conducted in April-May 2020. – Samuel Scott, series co-editor and Research Fellow at IFPRI.

Picture credit/ shutterstock

Since the first case of COVID-19 in India was reported on January 30, the number of reported cases in the country has spiraled to over half a million. Despite the government’s efforts at containment, COVID-19 has hit over 90% districts of India. The initial response to the pandemic was the imposition of a country-wide lockdown from March 25, a move that favored lives over livelihoods. While this measure has saved thousands of lives and provided much needed time for health system strengthening, it has rendered millions of people jobless, without income, and at risk of poverty, hunger, and malnutrition.

In May, more than 5.8 million jobless migrant workers from major metropolitan cities returned to their origins, mostly to Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. Suddenly, families have more mouths to feed, especially at a time when remittances have stopped and income from agriculture or other sources is affected by the lockdown.

A likely impact of reduced household incomes will be reduced availability, accessibility, affordability and quality of food consumed, especially for vulnerable socio-economic groups, women and children. In this blog, I discuss the ground situation, challenges and opportunities for India’s nutrition program in the time of COVID-19. The data is from the government’s Health Management Information System (HMIS) and the two recent phone surveys conducted by the Population Council Institute from April 3 to April 22, 2020, and Population Council Institute and UNICEF from May 13 to May 22, 2020 in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

Women are more likely to report food shortage and reduced intake

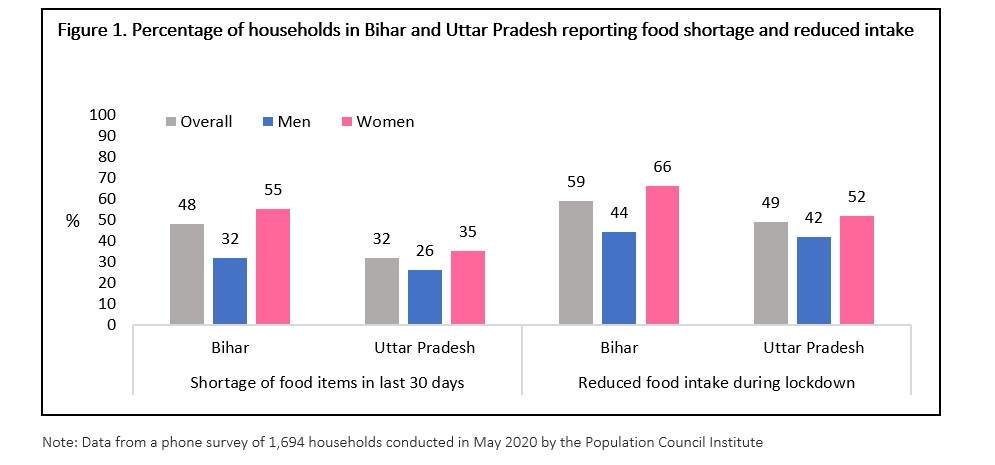

The lockdown has reduced food availability within households. Our survey of 1,694 households in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in May found that 32-48% of households faced a shortage of food items in the past 30 days, and 49-59% of households had to reduce their food intake during the lockdown (Figure 1). Eighty-two percent of those who reported a shortage of food items in their household, also reported a reduction in food intake. We also find gender differences in the responses. As compared to men, a higher proportion of women in our study reported food shortage and reduced intake. This is perhaps because men may be less aware of the food shortage as women in the household may sacrifice her share of food to sustain the daily food intake for the men in the family. It is well known that in large parts of South Asia, inequalities in intra-household food allocation are highly gendered, with women faring worse than men. During a pandemic, when households face food insecurity, these inequalities might further widen.

Diet quality is also compromised

Families who reported reduced food intake mainly compromised on eating fruits, vegetables and flesh foods, all of which are relatively expensive food. This finding is unsurprising as there is reduced incomes, and the food support through the Public Distribution System (PDS) consists of only grains and pulses. Pregnant women consumed three food groups on an average, falling short of the recommended five food groups. Dairy and flesh foods were the foods that pregnant women consumed least. These changes in consumption patterns may have downstream effects on anaemia, micronutrient deficiencies, and acute malnutrition in women and children.

Are vulnerable groups receiving support from government nutrition programs?

A myriad of existing nutrition programs under Poshan Abhiyaan aim to provide holistic nutrition to vulnerable segments of population, including women, girls, and children. However, reports suggest that the delivery of these programs was suboptimal even before the pandemic. Further, schools were closed, cutting off access to mid-day meals (MDM) for more than 116 million eligible children. Moreover, Anganwadi centers were not operational, presenting difficulties in the provision of supplementary nutrition services such as Take Home Rations (THR) to pregnant and lactating women.

I compared the HMIS data for 2018-19 and 2019-20 for the months of January, February and March in nine Empowered Action Group states, and found a sharp drop in the number of pregnant women who were provided free meals under Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakaram between February and March 2020, as compared to the same period in 2018-19. While it is possible that the decline in the number of beneficiaries in March 2020 may not reflect the true impact of the lockdown that was imposed towards the end of that month, it is also possible that the program delivery was affected even before the lockdown was formally announced.

Our study surveyed 1,374 young women in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in April. The findings showed that while more than half the surveyed women expressed the need for nutrition services, only 2% of them reported receiving these services. Unfortunately, availability of program data for April and May is also impacted by COVID-19, making it difficult to estimate the continued impact of COVID-19 on women’s access to nutrition programs.

In response to the pandemic, both Central and State Governments announced measures to ensure food security of the poor, such as direct cash transfers through existing schemes and additional grain allotment for three months. The Central government increased fund allocation to the MDM scheme and different State governments devised ways to ensure either home delivery of one time meals (Kerala) or ingredients (e.g. in West Bengal) or cash in lieu of meals (e.g. in Bihar). However, our May 2020 survey found that only 25-33% of eligible households in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar received THR and an even smaller proportion in Bihar received cash in lieu of mid-day meals. This suggests that government’s response to the crisis has been less than adequate.

Way forward

Available evidence indicates that the lockdown resulted in a reduction in the quantity and quality of food consumed and could serve to widen intra-household gender disparities in this regard. Support from existing government nutrition schemes such as THR for pregnant women and young children and school meals for school-going children needs to be prioritized as well as strengthened. In addition to a multi-level response to the issue, continued management of severely malnourished children, effective nutrition messaging that promotes balanced diets, adequate resource allocation for meeting increased demand for nutrition support, and effective delivery of supplementary nutrition are essential steps to preserve gains from years of nutrition programs. We have a huge opportunity to learn from the pandemic, and build effective and resilient systems of nutrition program delivery.

Rajib Acharya is an Associate with the Population Council’s New Delhi office. The opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the author.

This blog has been published as a part of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), South Asia, blog series on analyzing the impacts of the COVID-19’s pandemic on the sub-national, national, and regional food and nutrition security, poverty, and development. To read the complete blog series click here

New research from a Special Issue of Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy

The pandemic caused disruptions to both the supply of and demand for health services that persisted past the lifting of lockdown measures.

Public food transfer programs have traditionally been the most common social protection programs in Bangladesh