How COVID-19 may affect household expenditures in India: Unemployment shock, Household Consumption, and Transient Poverty

India’s unemployment levels have tripled and household income has suffered as a result of the COVID-19 shock. IFPRI researchers Manavi Gupta and Avinash Kishore use econometric methods to offer insights into how household consumption may be affected by this shock. Comparing households that did or did not experience job loss in 2019, they show that expenditures on durable items in wealthier urban households are affected the most, and that rural households are more resilient than urban households in terms of changing consumption patterns. Whether these findings hold true in the aftermath of COVID-19, a more severe systemic shock than previously experienced, remains to be seen. – Samuel Scott, series co-editor and Research Fellow at IFPRI.

On March 24, 2020, the Government of India imposed a strict nationwide lockdown to arrest the spread of COVID-19. The 12 week long lockdown led to a sharp increase in unemployment – and widespread loss of household incomes, especially in urban areas. The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) reported unemployment levels of 24-27% in April and May, up from 8-9%, before the lockdown started. Even people who have not lost their jobs are reporting income losses due to pay cuts and declining business profits. In a nationally representative survey of nearly 6000 households in May 2020, 84% of households reported decreases in income since the lockdown.

Research questions

In this blog, we attempt to answer several questions. How do households respond when a working member loses his or her job or when there is a reduction in family income? Are there differences across rich and poor or rural and urban households’ in terms of their response to such shocks? If households reduce their expenditure, what are the margins they make these adjustments on? These are important questions not only to understand and estimate the damage caused by the pandemic but also to design effective policy responses to mitigate the impact on households and the overall economy.

Data source and analytical approach

In the absence of reliable post-lockdown data on employment or consumption expenditure, we use the Consumer Pyramid Household Survey (CPHS) data from March to April 2019 to understand how households respond to employment shocks. These results only provide a lower bound estimate of the magnitude with which the lockdown has likely affected employment and household demand. The job losses in 2019 were idiosyncratic, while the lockdown is an economy-wide shock that has affected most Indian households. Besides impacting household demand via income constraints, it has also crippled supply chains, and its omnipresence makes it difficult for households to depend on their social networks as a coping mechanism. Thus, our estimates from the 2019 data only provide suggestive evidence of how unemployment under the 2020 pandemic may affect household consumption patterns but the actual impact is possibly much larger. Conducted by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, the CPHS covers a nationally representative sample of 175,000 households from all states of India. Households are surveyed every four months on a monthly recall basis to create high-frequency panel data on household consumption, income and employment status of household members.

To estimate the immediate impact of job losses on consumption patterns, we compare total consumption expenditure and expenses on food, education, health, and discretionary items (intoxicants, clothing, recreation, eating out) of households that experienced job loss (treated households) against households that did not face any job loss (control households). 6% households in CPHS reported that at least one member who was working in March 2019 had become unemployed in April 2019. We conduct this analysis for the entire sample as well as separately for rural and urban households. We also measure heterogeneity in responses to job loss across households at all deciles of monthly per capita consumption expenditure (MPCE).

Findings

Consumption in urban households is more sensitive to employment and income shocks than rural households

An episode of job loss leads to an immediate reduction in household consumption expenditure by 6.2%, but the decline is twice as large in urban areas (11.1% vs 5.1%). Similarly, a 1% decline in family income leads to an instantaneous 0.05% and 0.29% decline in consumption expenditure for rural and urban households respectively. To put this in perspective, a similar analysis undertaken by us using previous CPHS data shows that demonetization had a similar impact; consumption of urban households declined (almost 4%) more than rural households after the demonetization in November 2016.

Rich urban households report the largest declines in consumption

In rural areas, consumption expenditure of the poorest households declined the most after the shock, as we might expect. However, to our surprise, the opposite was true in urban areas, where it was the richest households that reported the biggest change in consumption expenditures. We can think of two possible reasons for this unexpected result. First, rich urban families have higher discretionary expenditures that can be easily given up after an employment or income shock. Second, as in the US, there are many “wealthy-hand-to-mouth” families in urban India, also with high earnings and spending, and not enough cash or liquid savings to smooth consumption after a shock.

Households cut expenses on durable items the most

Following a job loss event, we find large declines in household expenditure on durables (29.4%) and discretionary items (10.7%). More concerningly, however, unemployment leads to a decline in expenditures on health (15.3%), education (12.9%) and food (3.6%), which could lead to long-term consequences even if the shock is temporary. In addition to these reductions, households also reduce loan payments when faced with income loss.

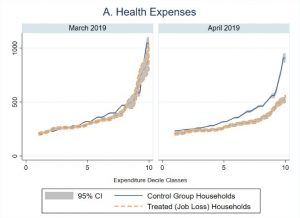

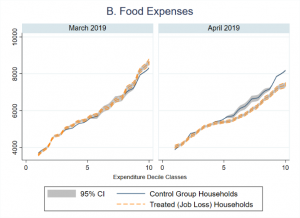

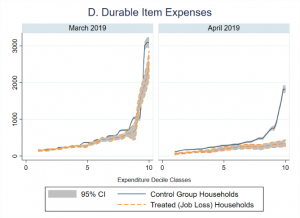

Figure 1 depicts the decline in household expenditure for some of these categories, before and after the shock. Households that experience a job loss show a significant decline in health expenditure compared to their counterparts, across most economic classes (Fig 1A). Food expenses decline more sharply for households above median consumption, i.e., for richer households (Fig 1B). Education expenses decline consistently for poor households (below median consumption) but show the severest drop among the richest households (Fig 1C). Likewise, durable expenses are cut down to a large extent by richer households (Fig 1D).

Figure 1: Impact of job loss on household expenses (INR) across consumption deciles classes

Note: The figures above graphically depict the local polynomial regression of expenditure on health, food, education and durables on different expenditure decile classes. The comparison is made between the two months – baseline (March 2019) and endline (April 2019), distinguishing between households that experienced job loss in April 2019 and those that did not.

Borrowing to ease consumption is not an option for most Indian families

Households rely on diverse types of credit arrangements to smooth consumption when there is an income shock. However, we find that after an employment shock, the probability of starting a new loan increases significantly only for households with multiple earning members. Perhaps, lenders find families where the only earning member has lost his or her job less creditworthy, but are willing to lend to families where at least one member is still employed. Unfortunately, most (77%) families in India have only one earning member, and this does not vary by urban or rural residence.

Government transfers help mitigate impacts

More than 700 million Indians received some cash transfer in 2019-20 from one or more of the 426 direct benefit transfer schemes of the government. 56% of respondents in the CPHS reported getting some cash subsidy from the government in March 2019. The average amount of transfer was INR 473 (3.7% of the monthly household expenditure). India’s cash transfer schemes are not designed as unemployment benefit programs. Even then we find a small, but statistically significant positive impact of the cash transfer on consumption expenditures after the job loss. The cash transfer mitigates the impact of the job loss.

Looking ahead: India’s urban families need more support to fight the economic impacts of COVID-19

Ray and Subramanian (2020) argue that the economic consequences of India’s lockdown could hurt people more than the direct effects of the pandemic itself. Our analysis of 2019 data shows that rural consumption is more resilient to shocks than urban consumption. This is likely to hold true for the COVID-19 induced economic crisis as well, as agriculture – the largest employer of rural workers and the mainstay of the rural economy – is one sector where total employment has increased after the lockdown.

Most of India’s welfare programs, however, have a clear rural bias because there is more poverty in rural India than in urban India. The Central Government’s COVID-19 relief package, called the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana (Prime Minister’s Welfare Scheme for the Poor), also directs disproportionately more resources to rural areas. Yet the lockdown has pushed millions of urban households into transient poverty. Most of these newly poor families are not covered by any social safety net programs. There is an urgent need for central and state governments to expand their existing safety net programs to cover newly poor households as well. This will help address not only an important humanitarian and social issue, but would help speed up economic recovery to everyone’s benefit.

Manavi Gupta is a Research Analyst at IFPRI’s New Delhi office (NDO); Avinash Kishore is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s NDO. This blog is based on an unpublished paper titled, ‘Unemployment and Household Spending in Rural and Urban India: Evidence from a Panel Data’. The draft paper is available on request. The analysis and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors.

This blog has been published as a part of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), South Asia, blog series on analyzing the impacts of the COVID-19’s pandemic on the sub-national, national, and regional food and nutrition security, poverty, and development. To read the complete blog series click here

New research from a Special Issue of Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy

The pandemic caused disruptions to both the supply of and demand for health services that persisted past the lifting of lockdown measures.

Public food transfer programs have traditionally been the most common social protection programs in Bangladesh