Learning from earlier crises: ASEAN countries’ trade responses during COVID-19

Policies related to international trade and domestic marketing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic bear resemblance to the measures instituted in the wake of the 2008-2009 global financial and food price crisis. The authors describe the lessons that should be learnt from the experiences of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) countries, and suggest that their responses in 2008-2009, for instance on export restrictions and panic-buying, could have led to further increase in food prices and thus exacerbated the impact of the crisis. Instead, investing in timely information systems and garnering support from multilateral institutions such as the World Trade Organization and ASEAN Secretariat could help reduce the impact of this current economic downturn. – Kalyani Raghunathan, series co-editor and Research Fellow, Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division (PHND)

The merchants of Lok Baintan Floating Market, Indonesia sailed through Tabuk River after finishing their trade activities, before COVID-19 pandemic. Shutterstock/Eriz

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to several countries imposing lockdowns, disrupting global supply chains and restricting the movement of goods and labor. The case of ASEAN countries is no different. COVID-19 has resurrected trade issues and brought into focus earlier policy responses to the 2008 global financial and food price (GFP) crises. In this blog, we look at how ASEAN countries’ trade has been affected by COVID-19 related disruptions, comparing the current scenario to the GFP crisis of 2008.

Restrictions on food exports during 2008 GFP crisis

During the 2008 GFP crisis, increase in food prices resulted due to a combination of various factor such as high oil prices, growing use of biofuels, bad weather, and country-specific restrictive trade responses, including export duties, export controls, and setting up minimum export prices. These restrictions not only resulted in lower food supplies, but also led to panic buying among food deficit countries, which may have led to further increase in food prices.

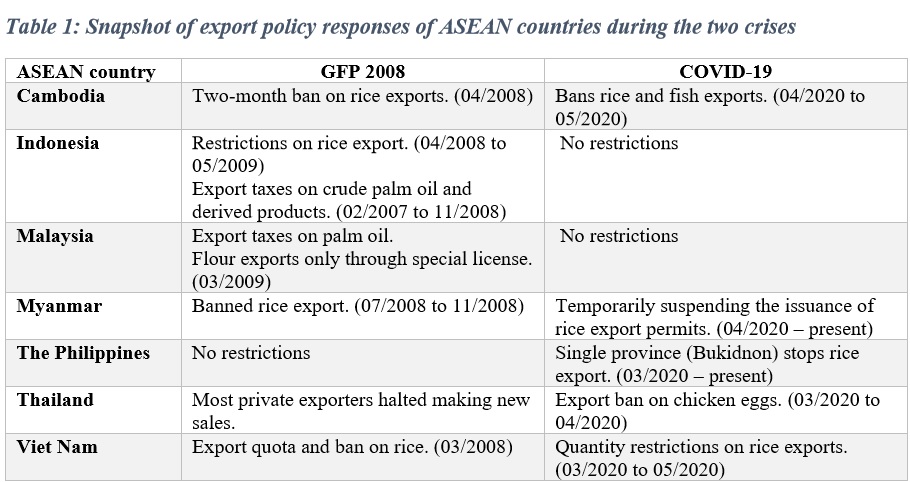

The two most traded food commodities within ASEAN, in the three-year period ending in 2008, were rice and palm oil (non-crude) that have contributed to almost one-fifth of the intra-ASEAN food trade. Both commodities were subject to government export restrictions during the GFP crisis (Table 1).

During 2008/2009, rice exports (in deflated value) of Thailand and Viet Nam fell by 61% and 13%, respectively. Exports were affected by a halt in sales by rice exporters in Thailand, in responding to increasing global rice prices and the minimum export price regulation and the ban imposed by Viet Nam. These policies had adverse effects on exports from Thailand and Viet Nam to other countries in the region, especially to the Philippines, which resorted to panic buying. The Philippines in fact launched a series of tenders for rice equivalent to one year of normal imports between December 2007 and March 2008. Rice prices surged to almost $800 per ton by June 2008 compared to $300 per ton in late 2007. Rice export restrictions ultimately contributed to almost half the world price surge in 2007-2008.

Source: GFP 2008 responses (Cambodia, Malaysia, and Viet Nam; Indonesia; Malaysia; Myanmar and Thailand); COVID-19 responses (Laborde, Mamun, and Parent 2020; Market Access Map 2020).

Note: Information on COVID-19 responses assessed on June 5, 2020.

Cambodia’s trade response followed the same pattern, although with some difference in terms of timing. Like other countries, Cambodia had also initially imposed a ban on rice exports. Later, in the second half of 2008, it lifted this ban to take advantage of high international prices and in anticipation of a market correction triggered by Japan’s decision in June 2008 to re-export its rice stocks. Cambodia benefitted by opening up, with rice exports increasing by 50% between 2008 and 2009.

Exports of palm oil, the second most traded commodity within ASEAN, after rice, were also discouraged. Indonesia and Malaysia – the two largest exporters of palm oil globally – imposed export taxes to make oil available for domestic consumption and prevent domestic prices from increasing. These policies had sizable effects, with palm oil exports from Indonesia and Malaysia to other ASEAN countries declining by 53% and 29%, respectively.

ASEAN countries’ food trade policy responses during the GFP crisis disrupted food supplies and hindered ASEAN integration. Chandra and Lontoh (2010) state that while ASEAN countries made various commitments in multilateral, regional and bilateral forums, government interventions continued to offset these commitments for a small set of products, including rice, cereals, sugar, meat and dairy.

Response during COVID-19: Call for self-sufficiency

During the current COVID-19 pandemic, ASEAN countries have adopted similar export restrictions to those adopted during the GFP crisis (Table 1), generating concerns about similar effects on food deficit ASEAN countries, which had instituted self-sufficiency policies in the aftermath of the 2008 food price crisis.

The Philippines has taken a different approach to rice policy in response to COVID-19 than what it adopted during the GFP. This is due to a policy change that fortuitously happened right before the pandemic, whereby the Philippines’ rice reforms lead to ‘tarrification’ of rice imports and the removal of the quota on imports. The quota was replaced with a general minimum tariff of 35% on rice imports, the proceeds of which are to be reinvested in the rice sector to enhance its competitiveness.

In a sharp contrast to the country’s response in 2008, the Philippines’ response to export restrictions during COVID-19 has relied far less on rice imports through government-to-government purchase agreement, launching instead the ‘Plant, Plant, Plant Program’. This program aims to raise milled rice production to 13.5 million tons, which constitutes 93% of the country’s total demand. The reform of Philippines’ rice trade policy can be seen as having set the stage for changing the policy context from self-sufficiency to self-reliance. Nonetheless, the fragility of regional food trade during shocks in a crisis like COVID-19 remains a major potential concern for ASEAN countries, in terms of economic integration and food security.

Lessons learnt from the crises

The following lessons can be drawn for ASEAN food trade from their experiences to better prepare for future shocks:

- During a crisis, information sharing is essential for effective policy and stock management. In 2002, ASEAN created the ASEAN Plus Three Food Security Information System (AFSIS) to provide timely, reliable, and early warning information to ASEAN countries for better planning and implementation of food security policies. However, the quality and reliability of AFSIS’s data remains a concern to date. ASEAN needs to strengthen such institutions to foster greater cooperation on regional food trade.

- During crises, the role of multilateral institutions such as the World Trade Organization and ASEAN Secretariat are important in tempering unilateral trade restrictions and bringing greater stability to intra-ASEAN trade. Undisrupted trade may lower the incidence of distortionary government interventions.

- When countries with a food surplus insulate themselves through trade restrictions, they induce panic buying in food deficit countries. This puts upward pressure on food prices, which can lead to food security concerns and result in social unrest. Instead of imposing restrictions during crises, countries may appeal to the regional food bank APTERR to ensure adequate food supplies to the ASEAN countries by taking stock of the food production and demand in the region.

The experience of ASEAN countries during the 2008 GFP crisis provides several lessons that can be applied to the current pandemic. Countries that learn from this historical perspective would be better placed to mitigate the unintended consequences of overly zealous restrictions on inter-country trade.

Manmeet Ajmani is a Research Analyst at IFPRI’s New Delhi Office (NDO). Fabrizio Bresciani is the Lead Regional Economist (Asia and Pacific Division) at IFAD, Rome. Devesh Roy is Senior Research Fellow at IFPRI’s Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH). The analysis and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors.

This blog has been published as a part of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), South Asia, blog series on analyzing the impacts of the COVID-19’s pandemic on the sub-national, national, and regional food and nutrition security, poverty, and development. To read the complete blog series click here

New research from a Special Issue of Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy

The pandemic caused disruptions to both the supply of and demand for health services that persisted past the lifting of lockdown measures.

Public food transfer programs have traditionally been the most common social protection programs in Bangladesh