BY RASMI AVULA, SUPREET KAUR, PURNIMA MENON

India’s progress on scaling up health and nutrition services was remarkable in the pre-pandemic period. The gains made in these past years are important to preserve. Rasmi Avula, Supreet Kaur and Purnima Menon discuss the importance of existing state capabilities and the role of frontline workers in providing health and nutrition services in the context of response to COVID-19. - Devesh Roy, series co-editor and Senior Research Fellow with the CGIAR Research Program on Agriculture for Nutrition and Health (A4NH).

Health and nutrition counselling by an anganwadi worker in Saintala Block, Odisha, before COVID-19 pandemic. PC/ POSHAN Team

The COVID-19 pandemic seems to have ushered in a new order of life and has expanded its influence into every sphere of human existence. While it is raising havoc in the short-term, we are yet to fathom its long-term effects on health, nutrition, economy, local and global politics and policies. As we wait to see what lies ahead, the effects of current steps taken by governments to flatten the curve are impacting lives in multiple ways. This is particularly true for the most vulnerable groups, including pregnant and lactating women and young children, whose lives cannot be put on hold as they go through critical development phases.

As of May 11, India’s lockdown strategy entered its eighth consecutive week. The impacts are being felt through multiple direct and indirect pathways, including loss of livelihoods, reverse migration, and changes in access to health and nutrition services. While these may have a range of consequences in the immediate future, changes to nutrition and health care services could have long-term implications for the future generation. It is critically important that these programs are protected to keep up the momentum on the progress made over the last decade in improving health and nutrition outcomes.

State capability for health and nutrition programs was never more important

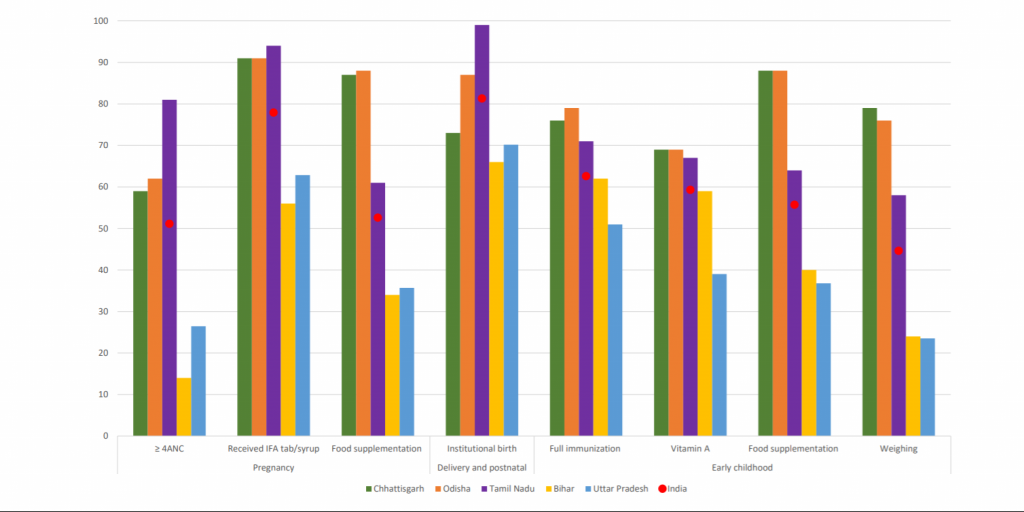

India has a robust policy framework for nutrition that covers most of the evidence-based interventions in the first 1000 days, essential for improving pregnancy outcomes, and preventing growth faltering and poor development among children. These interventions are delivered through its two large-scale national programs – the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) and the National Health Mission (NHM). In 2016, at the national level, the highest level of coverage for key nutrition interventions was about 65%, and for most interventions, coverage was just about 50% or less. There is, however, a high state-level variability in the coverage of these interventions. For example, while the coverage of most maternal and child nutrition-specific interventions was better than the national average in states like Chhattisgarh, Odisha, and Tamil Nadu, it was much lower in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh (Figure 1). These inter-state differences stem from variability in state-specific approaches to support implementation of ICDS and NHM programs, despite a common national framework and guidance. This inter-state variability gains further prominence in the context of COVID-19 response, where India is taking steps to enforce social distancing, including making changes to how its social sector delivers essential services. The impact of these measures on the most vulnerable groups who are dependent on these two flagship programs for their health and nutrition needs is unknown at this point. However, given that physical distancing in service delivery is likely to stay, the implications of some of the program changes could be far reaching in the long run.

Figure 1. Coverage of selected interventions across the continuum of care in some states, in 2016

In response to the national government’s lockdown notification in late March, states have issued orders pertaining to the ICDS and NHM services. In most states, ICDS centers were closed and several services were disrupted. For instance, provision of hot-cooked meals, home visits, and growth monitoring services have been suspended. On a positive note, however, in many states, frontline workers are home delivering these food supplements to those who are entitled to benefit from Take-Home Rations or to Hot-Cooked Meals under the ICDS Supplementary Nutrition Programme. As per the guidance from the state health department, community-based antenatal care services, and immunization services have been put on hold. Although these services are available at the health centers and hospitals, public transport shutdown may have made it difficult for beneficiaries, as most health facilities are generally not available at the village level. In these times of uncertainty, disruption to such critical preventive care services is likely to have serious implications, including rise in maternal and child mortality.

There is great dynamism in the policy environment today, with state guidance being issued every 2-4 weeks. Existing state capabilities are most likely to enable adaptation to the dynamic requirements of COVID-19 and subsequent responsiveness by district, block and frontline staff to the guidelines. States that have built their systems during non-emergency situations are likely to be able to respond relatively quickly to the changing demands due to COVID-19 and bounce back at the end of this pandemic. For example, states like Chhattisgarh, Gujarat, Odisha and Tamil Nadu, all considered to be success cases in service delivery, have invested in strengthening their implementation systems through long-term efforts. In the mid-2000s, these states complemented major national efforts like scale-up of ICDS, and introduction and scale-up of NHM with state-specific innovations. Stakeholders from various fields, like media, civil society, human rights commissions, politicians and bureaucrats, acted as catalysts and champions to support the changes. The situation may be quite different in other states, where existing capabilities and delivery mechanisms are not as robust. However, it is certainly possible that the crisis will force a greater investment in strengthening systems in the lagging states. Thus, scenarios can play out differently in different states, depending on the status of its infrastructure, staff capabilities, delivery systems’ efficiency, and responsiveness prior to the crisis.

As states attempt to mobilize existing systems to support COVID-19 actions and adapt to essential health and nutrition services, the role played by frontline community workers for health and nutrition programs has been key. To the extent the lockdown and physical distancing guidance allows, it is commendable that frontline cadres are delivering services as well as carrying out newly added COVID-19 duties. Frontline workers are expected to conduct home visits to document recently returned migrant workers, communicate COVID-19 related messages, check for symptoms and refer them to health systems. Such duties do carry some risks of contracting the virus that could negatively affect their relationship with the beneficiaries, particularly when COVID-19 positive cases are identified and referred to quarantine facilities. At the same time, they could also be seen by communities as a critical part of public health force dealing with the pandemic. The prior rapport that they shared with their communities could also help determine how this plays out through the course of the pandemic.

India’s progress on scaling up health and nutrition services was remarkable in the pre-pandemic period. The gains made in these past years are important to preserve. Reductions to services in the short-term leading to missed antenatal check-ups, immunizations, growth monitoring and lack of access to food supplements, can have long-lasting implications on pregnancy and child outcomes during the critical first two years. If services are further disrupted or if client population are too afraid to access services, there is a risk of resurgence of other infectious diseases, increased morbidity, and mortality, and for survivors, there can be short- and long-term consequences of poor physical growth and intellectual development early in life.

Keeping a close eye on health and nutrition service delivery and uptake is essential to prevent backsliding on the National Nutrition Mission

Much progress has been made on ensuring health and nutrition services for mothers and children until now. It is, therefore, essential that we assess how policy responsiveness across India is evolving to ensure infection control and identify opportunities to mitigate the unintended consequences of choices made in these times of crisis. Continued vigilance of service changes is required to support the government in taking actions to support continued health and nutrition service delivery. Similarly, continued data and insights from qualitative research on how client population is using health services will help tailor essential services alongside pandemic preparedness.

In the end, improved quality and sustenance of high coverage of essential health and nutrition services will depend on the state of service delivery and use of these services. By using information on program adaptations across the country, together with data and evidence on the delivery and uptake of services to stimulate timely actions, the nutrition community will be able to support actions to ensure that India’s nutrition gains are not lost. Every day, more than 70,000 babies are born in India. Their future and that of India’s human capital depend on how well the nutrition community can support their families with essential services, especially in these times of crisis.

Rasmi Avula is a Research Fellow with IFPRI’s Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division (PHND); Supreet Kaur is a Senior Technical Expert at NITI Aayog; Purnima Menon is a Senior Research Fellow (PHND). The analysis and opinions expressed in this piece are solely those of the authors.

This blog has been published as a part of the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), South Asia, blog series on analyzing the impacts of the COVID-19’s pandemic on the sub-national, national, and regional food and nutrition security, poverty, and development. To read the complete blog series click here

New research from a Special Issue of Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy The pandemic caused disruptions to both the supply of and demand for health services that persisted past the lifting of lockdown measures. Public food transfer programs have traditionally been the most common social protection programs in Bangladesh